RCV IRV Hare

-

@jack-waugh, the main argument against instant runoff voting (IRV) in my mind is that it seems very easy to eliminate a Condorcet winner. The story line starts with an existing plurality system with two major parties (Duverger's law). Over time, the two parties will tend to converge to the center along any issue that is in play in an election. This leads to party members not being very happy with the results even when they win. This leads to challenges to both party establishments from their extreme wings. Under plurality, this can lead to parties losing due to the spoiler effect. Some of the arguments in favor of IRV claim it solves this problem because voters can vote for their extreme wing as their first choice and the party establishment alternative as their second choice, and the implicit assumption is the extreme alternative is eliminated in the first round and support flows to the "more electable" of the parties' offerings.

The problem with this argument is that IRV is being proposed in order to allow multiple alternatives, and the more choices their are, the fewer first place votes there will be on average for any individual alternative, and the greater the likelihood that alternatives in a crowded middle will be eliminated. Once that happens, we start seeing IRV electing fringe alternatives instead of moderates, which is almost exactly what we have now with plurality.

Note that this argument is against the standard IRV in which if there is no winner, the alternative with the fewest first-place votes is eliminated. The dynamic is much better in a variation of IRV called the Coombs method, which successively eliminates the alternative with the most last-place votes. (The fact that a single alternative can have both the most first-place votes and the most last-place votes seems to have made it a hard sell, but that's a different issue.)

A different argument against IRV [that was actually presented as an argument in favor of IRV, (Bartholdi, 1991)] is that strategic voting under IRV is so complicated that it is nearly impossible to determine the best strategic vote. The author's argument is that faced with the computational difficulties of determining the best strategic vote, voters will instead choose to vote honestly. To me, this line of thinking seems unsound, and I thus take it as just one more reason to avoid IRV.

I hope this helps you in your discussions.

-

I think the strongest argument is this:

Nearly all IRV-advocates and voters using IRV wrongly believe that it somehow is tabulated optimally and has no spoilers. If everyone transparently understood the IRV spoiler scenarios, they would not react particularly strongly to the cases where it arises. However, IRV is almost always oversold with claims that are false. People believe that winners always have majority support or that spoilers can't happen. Thus, IRV sets up a situation to risk losing the public's trust.

A system that violates people's basic intuitions is a system people will be suspicious of.

Because IRV spoilers are both hard to explain, hard to look at the ballots and understand, and violate people's intuitions, it is a set-up for the destruction of trust in elections and in voting reform as a movement in general.

This is far worse than the effect of the spoiler itself.

The most important feature of a voting system is that it is easy for people to understand the results and trust that the system is working and thus feel trusting of the democratic process overall.

-

@wolftune I agree with the gist of this but can't agree with this:

This is far worse than the effect of the spoiler itself.

We have had IRV in San Francisco for almost 20 years, and it hasn't caused any sort of destruction of trust. I find the ballots to be pretty awkward, and a bit frustrating when you've only heard of one or two candidates.

But all evidence is that it is a net positive, and that most San Franciscans see it that way. I find this article on "gaming" IRV interesting:

https://www.vox.com/polyarchy/2018/5/14/17352208/ranked-choice-voting-san-franciscoKey quote:

How politicians “game” ranked-choice voting is exactly how politics should work...

To “game” the system in a ranked-choice voting election, the basic strategy is to try to appeal broadly and say, I’d like to be your first choice, but if I can’t be your first choice, I’d like to be your second choice.I'm of course all for advocating for better methods than IRV, but if it is a choice of IRV vs. regular plurality, I'd pick IRV any day.

This is another article also on Vox describing how IRV has functioned here over the past 2 decades, that I think is pretty good:

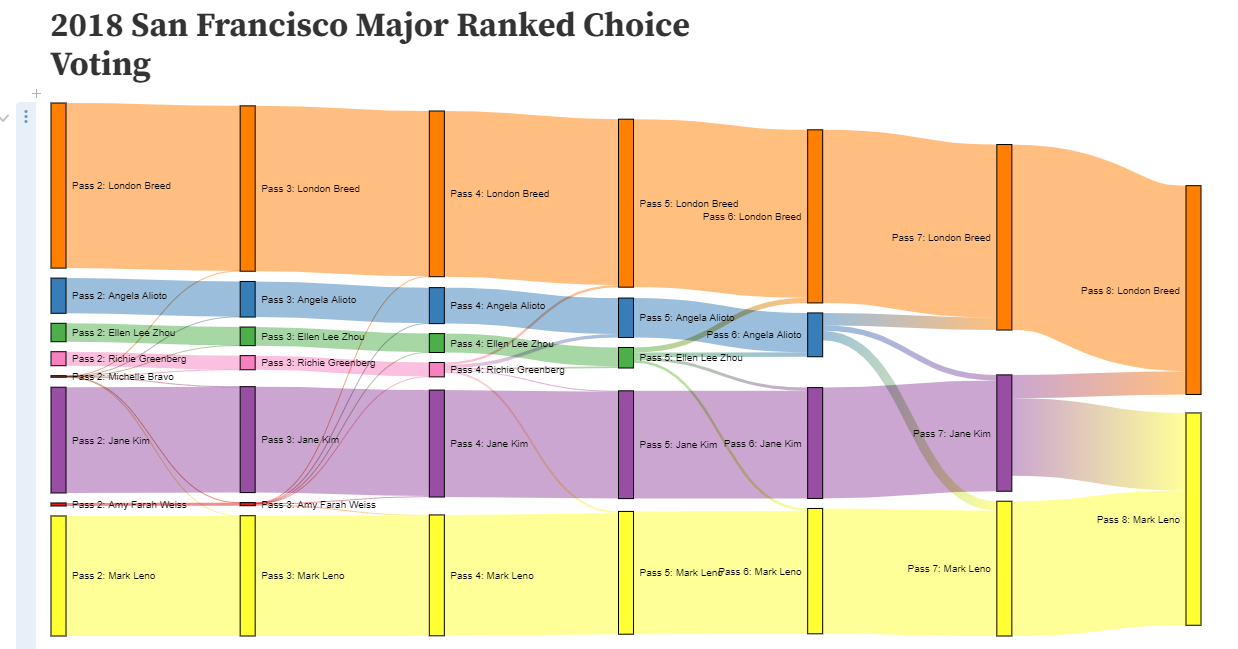

https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/7/24/20700007/maine-san-francisco-ranked-choice-votingI'll also add that a big part of increasing trust in a voting system is having good ways of communicating results to the public. I particularly like this chart showing how the IRV election for London Breed played out:

It is interesting in that it makes clear certain things that aren't so clear in other ways of expressing results, including Condorcet matrices.... for instance it clearly shows how most of Jane Kim's votes went to Mark Leno. It is clear that Mark Leno would have done a lot worse in a plurality race, as Jane Kim would have been a spoiler.

-

@Sass, please weigh in on this topic.

-

@jack-waugh The biggest organization that advocates for Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting says that it doesn’t help to elect third-party candidates.

https://www.fairvote.org/third_party_and_independent_representation

Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting only eliminates spoilers in favor of electing the correct duopoly candidate. When a voting method has high voting splitting, being a spoiler is about all of the power minor parties have over major parties to keep them accountable. It’s not much, but it’s something. Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting takes away what little power minor parties currently have over major parties, leaving the duopoly entirely unchecked rather than mostly unchecked.

To demonstrate, think about it from the perspective of a Republican candidate in a close race against a Democrat under Choose-one Voting. Some savvy Libertarian starts drawing away your voters. In order to ensure you can beat the Democrat, you have to concede something to the Libertarians instead of sticking with your party line. Under Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting, you don’t have to worry about that because the Libertarian votes will just transfer to you after the Libertarian candidate is eliminated. The same dynamic happens between the Democrats and the Green Party. In fact, half of what the Green Party talks about is how to get the Democrats to shift, not how to win elections.

When vote splitting remains in a duopoly, the spoiler effect is arguably a necessary evil. The solution is not to mitigate the spoiler effect — the solution is to eliminate vote splitting, which Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting doesn’t do because it’s really just iterated Choose-one Voting. Ultimately, the problems of Choose-one Voting can’t be solved by iterating it over and over again.

I could keep going, but whatever their goals are, demonstrate clearly that Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting doesn’t address them.

-

-

@jack-waugh said in IRV:

@sass, @rob says that in hundreds of elections, IRV elected the Condorcet winner except in the one instance in Burlington, Vt.

Yes this is true. 440 elections, all had a Condorcet winner. One of them didn't pick that Condorcet winner.

I think the differences would be pretty subtle between RCV (IR) and a ranked ballot Condorcet (such as Ranked Robin or Copeland//IRV), in terms of how they played out, how parties were affected, whether people tried to vote stragically, etc.

Where's the evidence otherwise? Unless Burlington burned to the ground during the time the wrong person was in office.....I'm just not seeing it.

-

@rob We talked in my open democracy discussion last Tuesday, but just so it's down in text, I'll reiterate a few points I made for anyone reading.

In elections with only two competitive factions, any voting method would elect the Condorcet winner basically every time. Even with the hundreds of Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting elections in modern US history, only a tiny number of them have had 3+ competitive factions, and most of those did not elect the Condorcet winner.

Electing the Condorcet winner is irrelevant when the elections aren't competitive. Ranked Choice (Instant Runoff) Voting clearly doesn't promote competitive elections if for no other reason than its hyperfocus on (false) majority. If a candidate only needs to get half of the electorate to support them in order to win, then they have every incentive to polarize every issue, locking down half of the electorate while ignoring the other half. What makes Score elections competitive is that there is no minimum threshold candidates need to get over to guarantee a win -- they actually have to beat every other candidate, even if another candidate has support from 70% of the electorate; it's a race to the top, not a race to 50%+1.

-

then they have every incentive to polarize every issue, locking down half of the electorate while ignoring the other half.

The evidence does not support this claim. In fact, the opposite seems to be true.

Early evidence is promising that IRV makes primaries work better in avoiding polarizing candidates and evidence supports at the local level that IRV changes how candidates campaign to be less negative and more civil

-

@andy-dienes Do you believe those gains are sustainable?

"In the 2014 survey, the gaps between resident perceptions of three indicators of campaign negativity in RCV and non-RCV cities were narrower than they were in the 2013 version..."

I believe that when voters and candidates are honest and excited, such as the first few cycles after IRV is implemented and FairVote convinces everyone they can finally be positive and honest, then IRV does perform better than Choose-one Voting and exhibits some of the positive effects that are often sold. However, as time goes on and the voters and candidates experience that their shiny new method keeps electing the same politicians as their old one, things will revert. That seems to show up in analyses of voter turnout in IRV jurisdictions after enough time.

-

@sass I think right now the data show IRV performs better than FPTP with respect to polarization, negative campaigning, and civility (which that rangevoting link does not seem to address---it looks like it's analyzing turnout). Speculating that those advantages are not durable is just that: speculation. Maybe we can revisit the question a few years down the line when we have more data.

And just by the way, I think ending polarization and negative campaigning and fostering civility is the most important thing that electoral reform can achieve. Ultimately I see a democratic process as serving two functions

- aggregating preferences from voters into a single platform

- creating a governing body that the populace consents to be governed by, and the voters feel is a fair choice

I think voting wonks and mathematicians often tend to focus on 1., but personally I believe 2. is the much more important aspect of a democratic process. If you gave me the choice between "FPTP in single member districts, but we magically make everyone reasonable, civil, and not polarized" vs "some perfect Condorcet / Score method and also proportional representation, but voters are unreasonable, uncivil, and polarized" I would pick the former without hesitation.

-

@andy-dienes I agree that it's mostly speculation at this point, though I have seen other papers and reports suggesting it's not that I need to find again.

I think the point about voters feeling like they have a fair choice needs to be qualified: it's important that we use systems that won't cause that feeling to backfire down the road. If voters like it at first, great. But if we're lying to them to make it that way, then when they inevitably discover the truth, we may end up in a worse place than where we started. It's important that we set ourselves and society up for success the first time, otherwise morale for voting method reform could be destroyed for a generation or more.

-

-

@andy-dienes said in IRV:

@sass said in IRV:

It's important that we set ourselves and society up for success the first time,

And I'll add to what Andy said, I think that approach sounds nice but it may be unrealistically idealistic.

In the US, the "first time" might be the Constitution, ratified 234 years ago. It had compromises like considering some people to count as 3/5ths of other people. (and those "lesser" people weren't allowed to vote). They did what they had to do to move forward. While that example is a pretty extreme one, there are a huge number of things that people wisely compromised on so that they could make progress.

Most of the places we can get a new election method implemented have already had their "first time", which was choose-one plurality. Moving them to RCV-Hare is a whole lot easier than moving them to RCV-something-that-no-one-has-tried-yet. Regardless, it won't be their first time.

I'm all for putting better methods out there as options. In fact, I would love to see some Condorcet advocates put together a proposal for, say, San Francisco, where it would be a small step forward from the RCV-Hare that has been used here for 17 years.

I'm also all for us putting our argument that Condorcet is better than IRV to FairVote, but in a way that allows them to keep calling it RCV, and allows them to allow potential new "clients" (i.e. governments that are considering adopting RCV) to pick whichever one they are comfortable with.

The funny thing about this (well, ironic, rather than haha funny) is that we, of all people, should be advocates for compromise approaches rather than "my way or the highway".

But going back to the whole "evidence" thing.... I haven't seen evidence that IRV-Hare does any of these bad things that you speculate that it will.

-

-

I'm also all for us putting our argument that Condorcet is better than IRV to FairVote, but in a way that allows them to keep calling it RCV, and allows them to allow potential new "clients" (i.e. governments that are considering adopting RCV) to pick whichever one they are comfortable with.

Well, I didn't argue for it, but I asked "FairVote" their opinion of RCV IRV bottom-two runoff, on Twitter. And to my surprise, they responded.

-

two competitive factions,

Are you talking about factions among the candidates, or factions among the voters?

not a race to 50%+1.

That's an absolute majority. Is there any seriously-proposed system that won't elect a candidate who has majority support (as their first choice), provided that the majority knows they are the majority and chooses their strategy in a way that takes that into account and is aimed at winning?

-

@jack-waugh Interesting that you got a response.

They say "IRV & bottom-2 runoff will usually have the same result but different campaign incentives. IRV rewards those w/ strong 1st choice support. Bottom-2 rewards those who avoid polarizing stances. We like IRV since it encourages real stances, not just campaigning to avoid the bottom"

It's really odd for them to claim that people would campaign differently when both methods "usually have the same result." If they have the same result in 339 out of 440 elections (which they proudly proclaim in multiple articles).... why would campaign incentives be so different?

Also odd that what they are arguing here seems to be the exact opposite of what they argue elsewhere. They are basically saying "Polarization is bad. Our voting system is better than others, because ours doesn't polarize people like those other systems do. Except, the reason we're better than Condorcet compliant systems, is that those systems have the exact same effect of reducing polarization.... but they do it even more than we do, and that's probably just too much".

I don't see how that makes sense. They really are talking out of two sides of their mouths.

-

@rob so I suggest you respond to them on Twitter.

-

@Sass, it's almost time for the realtime discussion that you regularly host. I intend to use the opportunity to put the following questions to you.

I have a question or two arising from what you and Rob B. have been saying back and forth. You distinguish the historical votes in the US where we have better ballot data than just what Choose-one Voting gives, as to whether they involved competition among more than two factions. Are those factions among the candidates, or factions among the voters? And how do you discern whether such factions existed for a given one of those elections?