Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?

-

@rob I think you could consider two groups of people such as those who have reasonable confidence that they are "adequately represented" in government, versus those who have reasonable confidence in the opposite direction. Then maybe there’s also some middle zone of suspicious, uninformed and misinformed people, and you could lump them into the mix. But I think we want to make the first of those groups as large as feasible and the second of those groups as small as feasible.

Obviously what constitutes adequate representation to a person is highly individual and depends on values and special interests, but it has a pretty unequivocal normative meaning once hypocrisy is removed. I think the second group is pretty close to what I would consider “the minority,” even though it has nothing to do with whatever fraction of the electorate it constitutes. PR even with parties seems to pretty decently address adequately representing a much larger fraction of the current minority than the present situation could hope to accomplish.

Also, there just has to be some kind of non-compensatory means of narrowing down the pool of candidates. I think political parties and primaries are reasonable and I'm not sure how else it would be done. The problem to me is a small number of large parties with a serious lack of accountability to public interests, not necessarily the very existence of parties. It would be ideal to be able to have a smooth spectrum of choices and the ability to elect based on the candidates alone, but I don’t think that can be accomplished without untenable sacrifices in efficiency.

When it comes down to it, potential candidates need to gain recognition, support and traction with a significant base, otherwise they have no chance of even getting on the map, since there is limited bandwidth. Granular parties don’t seem problematic to me, I think particularly binary ones though just in theory don’t have enough resolution to represent public interests, even ignoring externalities like polarization.

-

Just to expand once more:

https://twitter.com/mcpli/status/1574795032967712773

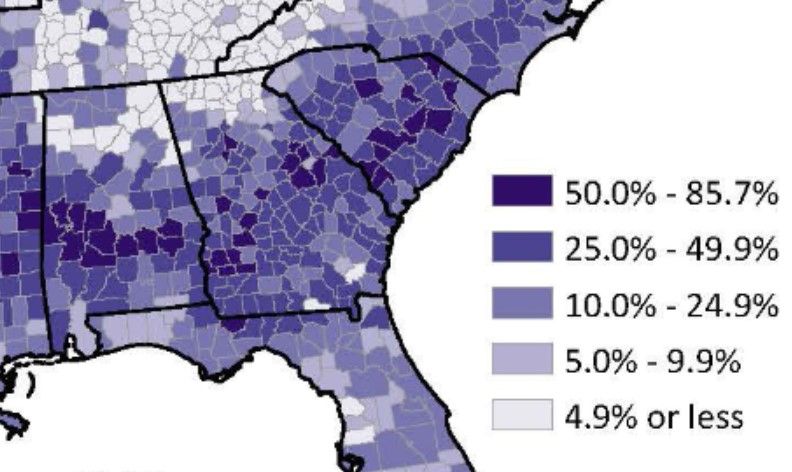

Check out the gerrymandering shenanigans happening down south *right now*

Due to incredibly racially polarized voting, Black voters can get a majority in only a single district. This is not an effect of FPTP vs Condorcet vs Approval vs whatnot---since we are talking about true majorities here the results will all be the same.

Proportional representation means that gerrymandering like this is impossible, or at least significantly more difficult and for less potential impact.

-

I'll put my TLDR at the beginning, but the rest of this post (which of course I wrote first) supports it in some detail.

- "outlier" is a more generalizable and clearly-defined concept than "minority"

- "equal power to move the results toward their preference" is a more generalizable and clearly defined concept than "equal representation"

- You don't need to bring in parties or multi-winner positions to make sure outliers have equal power to move the results toward their preference

So....

@cfrank said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

I think you could consider two groups of people such as those who have reasonable confidence that they are "adequately represented" in government, versus those who have reasonable confidence in the opposite direction.

Sorry but I don't understand that distinction. Based on what the voter's themselves have reasonable confidence in? If we can't define the concept in non-vague terms, how would we expect voters to have a reasonable or meaningful perspective on it?

Maybe you could explain it in terms of the temperature example I keep returning to: that is, something where there is a variable value and voter's individual preferences are single peaked. (making it more mathematically "pure" to ease analysis)

If someone happens to prefer the thermostat be set at 69.5 degrees, and 70 degrees happens to be the median preference (and therefore the "winner" under reasonable voting methods, including Condorcet), does that person have more "representation" (*) than the person who prefers 65 degrees?

I would describe the 65-degree person as an "outlier," but minority is obviously not a good way of putting it, since the term "minority" is dependent on a specific granularity/ quantization. Outlier is a concept that can be generalized in a way that "majority/minority" can't.

And I'd argue that both people have equal voting power, since each pulls the result in their preferred direction an equal amount. I'd call that "equal representation", or at least the closest equivalent that can be described in non-vague terms.

And I'd also argue that the exact same effect applies to voting for human candidates (with good, "median seeking" methods such as Condorcet). Example: 10 candidates are running for a position as city budget director. A minority of the electorate, 20%, wants a million dollars a year put into fixing the potholes in the roads. The other 80% want only $400,000 spent on that. Because it is Condorcet, the effect of those 20% is to elect a candidate that wants to spend, say, .5 million rather than one that wants to spend only .4 million (that would be elected if not for those 20%).

(And of course, more realistic is that there isn't really a clear minority or majority, since each person has different preferences. And, there are issues beyond fixing roads that influence voter's preferences. )

The point is, a voter that is in the "minority" (for whatever that means) has just as much influence on the outcome as a voter in the majority. You don't need to bring in parties to help with that. And this is true whether there are multiple candidates, or just one, or where the city is split into districts and each district gets to elect a single representative. It still works. Obviously the fewer candidates that are running, the less mathematically accurate it will be (in terms of picking the exact median budget), but hopefully you see the point here, which is that it should converge on the median, and all voters had equal pull.

I don't see how basing things on whether voters "are confident that they are adequately represented" narrows things down or clarifies anything, though, even if you assume they aren't being hypocritical. It just kicks the can down the road.

You and @Andy-Dienes are for more math-educated than me, but hopefully you can understand why I'd like something a bit closer to being possible to plug into an equation. I don't think the concept of minority/majority, or of "degree of representation" do that at all. They just seem very vague and hand-wavy, and they don't generalize well to situations with nuance and real-world messiness.

* or whatever the equivalent word is when we aren't actually speaking of a multitude of representatives per se

-

@rob said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

They just seem very vague and hand-wavy, and they don't generalize well to situations with nuance and real-world messiness.

I don't think it has to be hand-wavy whatsoever---it's just how we tend to talk about it here. Try looking at definitions like Proportional Justified Representation. Very formal.

-

@rob I think something we agree on, although we might express the concept differently, is that what it means to be properly or adequately represented in government or in general, whether absolutely or to any given degree, is not fully clear. To me the meaning of representation appears to hinge on the meaning of consent, which is heavily social. A functional definition or acceptable proxy of that social concept to apply to voting is basically a pillar of the discussion here.

Correct me if I mistake your view when I suggest that you are more or less alleging that agreement on a “reasonable” procedure is in itself an acceptable proxy for consent to representation, and you have illustrated your conception of what constitutes a reasonable procedure with analogies and well-defined criteria such as Condorcet compliance—Because such a procedure is reasonable, then if any such procedure is agreed upon, problems relating to adequacy of representation are effectively solved. Is that accurate?

If so, then I think this is one instance where we disagree. To me, adequacy of representation is an outcome issue, and explicitly not a procedural one. In my opinion it is highly dependent on context whether a single winner method is appropriate to achieve representation of any degree, even if it is for example a Condorcet method. A simple poll on the quality of representation voters receive from government officials on something like a “very poor,” “poor,” “fair,” “good,” “excellent” scale could formalize those feelings in any case. I would be very surprised if a PR system did not outperform a single-winner system in such a poll almost always.

Single-winner systems are still necessary for the delegation of distinct executive roles, but I don’t think they can be very effective in establishing good representation. And the more I think about it, the more merit I feel in @Andy-Dienes’ comment about single-winner systems and Duverger’s law.

-

@andy-dienes I looked at the Wikipedia article, and didn't see the things I discussed above defined.

Specifically, what is meant by "representation"? I would be interested in a definition that is generalizable, such as to situations where voters might have nuanced views on multiple issues. Same with "majority" and "minority". The words as I understand them only apply to very specific scenarios which I would consider unrealistic, such as binary choices.

I do notice that, on electowiki, it says "In the case of non-partisan voting, the definition of proportional representation is undefined". That seems to be getting at what I am trying to say. I take it further, as I find this assumption that parties must exist and be considered a prerequisite to be.... how do I say this? Offensive? Maybe that's too strong. But I don't like it and it doesn't align with my way of looking at group decision making, in the abstract.

Here's the best analogy I can come up with right now. Say I am looking at cars, and want one that is economical to drive and minimally damaging to the environment. And all the terminology used for comparison includes terms like "miles per gallon" and "smog rating" and such. And I keep asking, "why are you assuming it must use gasoline and be internal combustion?" They've basically painted themselves into a corner with their terminology, so they can't even evaluate electric cars -- at least not on the same criteria-- because they've made a bunch of (very limiting) assumptions up front.

That's how I feel about this assumption of parties, and the usage of terms like "representation" and "majority/minority" that only make sense with the assumption of parties (and seemingly with a bunch of other limiting assumptions as well, such as that each voter and each candidate is perfectly aligned/centered within their party).

I see parties (as opposed to special interest groups) as being mostly-unfortunate by-products of some electoral systems, not prerequisites to electoral systems. I'm not saying they must go away entirely or anything like that, but I don't think we should take them as a given, or define concepts around them, which PR seems to do.

-

@cfrank said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

Because such a procedure is reasonable, then if any such procedure is agreed upon, problems relating to adequacy of representation are effectively solved.

No I don't think that is an accurate way of stating my view. It's not whether the procedure is agreed upon, anyway. I think some methods are better than others. I hate to keep saying "Condorcet compliance" because as we all know that isn't perfect itself (although it is pretty good). But we want something that minimizes vote splitting.

I also don't like using the term "adequacy of representation" because I still don't feel that "representation" is fully defined in a generalizable way. We could be voting directly on an issue. Or if we are voting for, say, president or mayor, which aren't "representatives" per se. (I might be more interested in their competence and charisma than whether they are advocating for particular issues that I care about)

I guess I just prefer we stop using the word "representation" as if it is a measurable thing, at least until is it defined in crystal clear terms that aren't dependent on such things as the existence of parties. I think there are better ways of describing what we are after.

@cfrank said:

A simple poll on the quality of representation voters receive from government officials on something like a “very poor,” “poor,” “fair,” “good,” “excellent” scale could formalize those feelings in any case.

I'd think that is too subjective and too much slop. Some people are bad compromisers, and will rate the results as poor if they didn't get exactly their way. And if the poll has any influence on how things play out, you have incentivized them be "squeaky wheels" and exaggerate their dissatisfaction.

I think a better way of measuring how well a system works is trying to measure whether each voter has equal "pull." This is why I would tend to use a "voting for a number" (or "voting for an N-dimensional point) scenario as a benchmark, where each voter is assumed to have a single-peaked preference. A "median seeking" method is what I'd want. If it truly is median seeking, it would be game theoretically stable and meet my idea of "fair." If that means "adequate representation" (in a case where you are electing representatives), ok, but I find the terminology both vague and not generalized enough.

(and you just aren't going to be able to measure this stuff meaningfully unless you try to minimize extraneous variables and make it a "pure" situation. Think of it like an engineer testing a car engine on a test bench rather than in a car driving down the road. Voting for numerical or geometrical candidates is always going to lend itself better to analysis)

What I am saying is that, to the best I can see, a median-seeking method would achieve all the important ideals of PR (e.g. all voters get equal say), even in elections where there are no parties involved. You just wouldn't use terms to describe them that refer to parties or that assume that voters and candidates fit into neat little groups.

Regardless, bringing it back to Duverger's law. Let's set aside human candidates for an example, that just complicates and obscures.

Say you've got a club that gets together regularly to see movies, and you vote on the movie. It's easy to see how, under choose-one, you are likely to have "parties" form, starting with people just saying to one another "hey, let's agree to vote on the same sci-fi special-effects extravaganza, so we we aren't stuck watching a lame chick flick". So you end up with the action-movie party and the chick flick party (or whatever, but it should tend to converge on two over time). That's all you need for Duverger's law to kick in.... a system that splits the vote and incentivizes people to defend against it by teaming up.

Do you think that would still happen when ranking the options? Would people bother teaming up? I don't see how it would. The incentive to do so would be vanishingly small, especially if using a method that minimized any spoiler effect / vote splitting (e.g. median seeking / Condorcet compliant methods).

If you think it would still be susceptible to Duverger's law, please explain how you think that would play out.

-

@andy-dienes said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

Splitting seats up by geography is one way to guarantee some amount of diversity, but doesn't it seem to you like sort of an arbitrary axis along which to slice people? Why not split seats up by income level? Or gender? PR lets voters choose which of these axes they lie on matter most to them.

One reason to split them by geography is simply that it is already done currently in most existing legislative bodies in the US. So my argument there isn't that geography is the best way, but simply that it already is in place and is therefore hard to change. I think putting a ranked method in place is a lower hanging fruit, because it requires the least change. Also, it applies to offices such as President, governors, mayors, and a whole ton of local offices.

My argument is that a good, median seeking method (Condorcet compliant, blah blah blah) would solve the problem just as well as using PR. (and probably better, especially if you are talking about party-list PR) It has the advantage in that it works fine when the numbers are small enough that you can't really get things proportional (e.g. Wyoming only has one representative in Congress, so what can you do there? What about senators where there are two per state? )

I guess the idea is that if you have 3 offices to fill, and the voters are an equal balance of liberal, conservative, and libertarian, it is just as good to elect 3 centrists as it is to elect one of each ideology. A liberal voter, instead of being represented by one of the three office holders, could be said to be represented by 1/3 of each office holder.

And of course, if there aren't a nice even division of positions that matches the number of offices, this system still works. And of course all the candidates aren't just going to be exactly in the center and clones of one another, but at the extreme, yeah.... centrist candidates that represent everyone.

And if it was like that, I don't see a lot of gerrymandering. Because if it is centrist candidates getting elected, what is the point?

And sure, you can do that with multi winner or you can do it with single winner (typically by district). I see advantages to both. But what I don't want to do is require there be parties written into the legislation. Someone can be liberal without being in the Democratic party. The point is that the parties should have less, rather than more, importance in elections that they do today. Third parties are great, but so are independents. And parties don't work very well when they try to be both national and local. (for instance here in SF the republican party doesn't really exist in local politics)

-

@rob said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

My argument is that a good, median seeking method (Condorcet compliant, blah blah blah) would solve the problem just as well as using PR.

Let's return to the example of what's happening in Alabama right now. How would using Condorcet solve the fact that Black voters are a minority in nearly every district, yet are a substantial percentage of the population?

-

@andy-dienes I spent many years in Alabama. Lotta racism there. But there's actually a good number of counties that are majority Black.

But yes I think Condorcet would help just as much or more than party-based PR. Extremists (including racist extremists... Mo Brooks comes to mind) would be less likely to be elected to office. The 27% of the voters that are Black would be able to "move the needle" in their direction, favoring candidates that are less racist and more likely to make improvements on issues such as racial equity and inclusion.

I think with party list PR, you'd be more likely to have both racists, as well as people far on the other side, in the legislature. I'd rather have people on neither extreme. The more polarized the legislature (even if polarized in more than two directions), the more anger and ugliness, and the less progress gets made. And less progress is generally a bad thing for underprivileged groups.

One other thing I should say. Black people are an obvious distinction, because in most cases, you are either Black or not Black, and it is seen as an important part of your identity. Under a PR system, would there be a "Black party"? If not, what good does PR do in this case?

But there are so many ways to divide people. When I was in Alabama, I was employed as a software developer. Software developers are also a minority. I was a dog owner. Dog owners are also a minority. I was over 6 feet tall. People over 6 feet tall are also a minority. Everybody is in tons of minority groups. I'm not trying to be difficult here, I'm just saying, dividing people into discrete groups and then trying to deal with it based on group isn't always helpful. Treating people as individuals, and giving everyone equal pull (as Condorcet methods tend to do) is.

So yeah, I'm curious why you wouldn't think Condorcet methods would help.

-

I do notice that, on electowiki, it says "In the case of non-partisan voting, the definition of proportional representation is undefined".

Electowiki is (largely) written by people who tend not to read academic research, and I would take anything you read there with a grain of salt. PR emphatically does have rigorous definitions---in fact there are multiple. My favorite is Proportional Justified Representation.

Black people are an obvious distinction, because in most cases, you are either Black or not Black, and it is seen as an important part of your identity. Under a PR system, would there be a "Black party"? If not, what good does PR do in this case?

Yes, in the case of Alabama, voters are incredibly polarized across racial lines and we should almost certainly expect to see a Black coalition. I also wish you would not equate PR with party-list PR, because while I do think party-list PR is fine, there are plenty of PR schemes which do not require parties.

That district map you sent is not the one I am referring to, which is being drawn this year and is heavily gerrymandered. It doesn't matter if you use the fanciest Condorcet method in the world when the districts are drawn like this---nonblack voters have a true majority in nearly every district.

Software developers are also a minority. I was a dog owner. Dog owners are also a minority. I was over 6 feet tall. People over 6 feet tall are also a minority. Everybody is in tons of minority groups.

Exactly! Yes yes yes. Everybody is in tons of minority groups---why not let people choose which of these minority affiliations matter most to them, rather than artificially slicing along geographic lines?

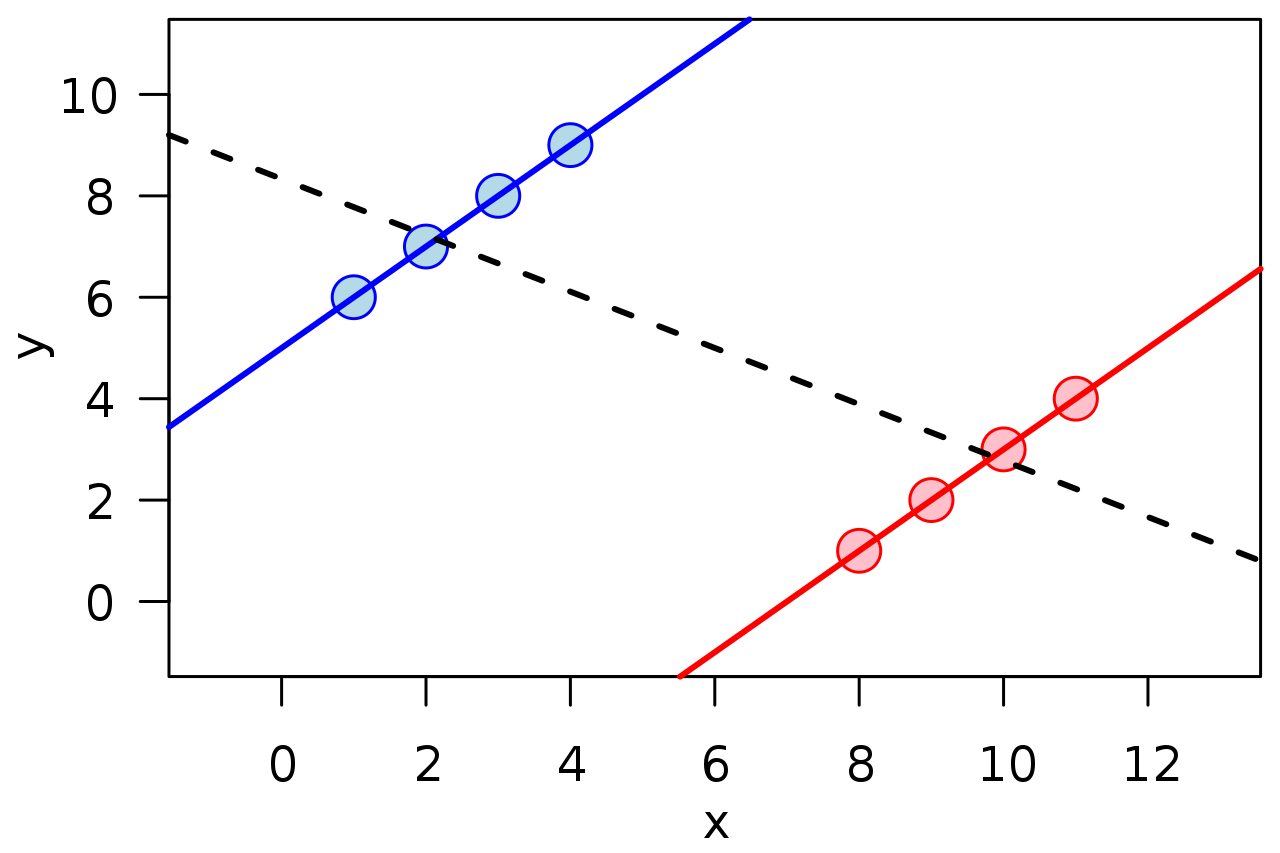

Generally speaking, gerrymandering is a form of Simpson's paradox

It does not matter if you find the "median in each district," since depending on how you draw the districts this can give you an overall outcome very very very far from the median of the entire electorate.

In your thermostat example, the median of [30, 31, 32, 70, 70, 70, 70, 70, 90, 91, 91, 92, 92, 93, 94] is 70, but the median of the medians of

[30, 90, 91], [31, 91, 92], [32, 92, 93], [70, 70, 70], [70, 70, 94] is 90. -

@andy-dienes said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

Yes, in the case of Alabama, voters are incredibly polarized across racial lines and we should almost certainly expect to see a Black coalition.

When I lived in Alabama, I was very put off by casual racism I ran into, and racism in general, and that was reflected in the way I voted. But I'm white, and there are a whole lot of things that affected my vote beyond that. So I don't think I identify with a "Black coalition". I want to express my view on the issues involved by voting for candidates that reflected my progressive views on racial issues, but I don't feel comfortable with having a choice between being a "Black coalition" voter and something else. So yeah that idea doesn't sit so well. Ranking candidates, where voters can take into account all the issues that matter to them and prioritize them, works much better for factoring in the views of many voters who are not necessarily Black but are progressive regarding racial issue.

@andy-dienes said:

I also wish you would not equate PR with party-list PR, because while I do think party-list PR is fine, there are plenty of PR schemes which do not require parties.

Yeah well my argument is mostly against party-list PR, I've tried to make that clear. That said, I don't quite understand what is "proportional" about PR if it doesn't refer to parties -- or at least distinct, hard-edged clusters. Can that be expressed in a simple sentence? (rather than a link to a long article where it isn't clear what part is relevant)

A median-seeking system that tends to elect candidates that are centrist is not really proportional per se, but it does have the effect of giving everyone equal pull. (I refer back to the "voting for a temperature by selecting the median preference" example... the system is fair and reasonable, but the word "proportional" doesn't apply because it doesn't first subdivide people into discrete groups)

I like systems that reduce parties and partisanship, by reducing the strategic need for them. Simply making it so there are more viable parties, to me, seems to solve mostly the same thing, but does so in a less elegant way that reduces the "accuracy," for lack of a better word. (by virtue of pre-quantizing along boundaries that can be arbitrary).

And since it doesn't apply to a whole lot of offices that are single winner by nature, it dilutes the message of the voting reform community and distracts.

But going back to non-party-list PR. Most of the justifications for even that kind of PR, still seem to assume parties in their arguments. When they suggest that some voter is in the "minority" that doesn't make sense unless you have subdivided people into groups. I assume the thinking is that that voter happens to most closely align with a party that is in the minority. But that is highly misleading because it has as much to do with where the boundaries of party are, as with how much the voter is an outlier compared to other voters.

And I still don't understand why you think a good ranked system is subject Duverger's law. To me Duverger's law is based on vote splitting effect of choose-one voting, not by whether or not it is single winner.

In the office thermostat example, a method that selects the median is not going to incentivize voters to organize into a cold-liking party and warm-liking party, creating a no-man's land in the middle. Nor would a Condorcet method. Choose-one certainly would, though.

@andy-dienes said:

Exactly! Yes yes yes. Everybody is in tons of minority groups---why not let people choose which of these minority affiliations matter most to them, rather than artificially slicing along geographic lines?

I'm not against getting rid of slicing along geographic lines (if possible....but I don't see how that is realistic with US government any time soon). But I don't see the need to re-slice them into other groups. I'd rather stop slicing people. Slicing is dividing. Dividing is divisive. I am against divisiveness.

Anything that slices people based on "what matters most to them" is probably going to mean no one in the middle. If I am a centrist, if I like everyone to get along, if I prefer less negativity, if I see things with nuance.... who represents me? There is very little incentive to create a middle ground party. Even if lots of people actually are in the middle ground.

@andy-dienes said:

In your thermostat example, the median of [30, 31, 32, 70, 70, 70, 70, 70, 90, 91, 91, 92, 92, 93, 94] is 70, but the median of the medians of [30, 90, 91], [31, 91, 92], [32, 92, 93], [70, 70, 70], [70, 70, 94] is 90.

That actually seems like you are trying to illustrate the exact reason why I don't like pre-clustering people into parties. Such clustering can have a very similar sort of distortion of the people's will.

If you are suggesting that single winner districts with Condorcet methods would lead to Gerrymandering, I'm not entirely sure how that sort of scenario would play out. Like how did it get broken up into groups such that it favored the hot-temperature liking voters?

Gerrymandering, by my understanding, primarily results from a two-party legislature that uses binary votes within it (such as to approve or disapprove the district lines). Therefore whichever party has more than 50%, gets to draw the lines. None of that is the case with Condorcet methods. Gerrymandering requires hard-edged parties, and is most significant when there are exactly two. The more you have the ability to elect middle ground candidates and independents, the less you should have to worry about Gerrymandering.

What you've shown is an electorate with three people who like intensely cold temperatures, five people who like a middle temperature (notably, with zero variation among them), and seven people who like extremely hot temperatures. It seems like you are trying to put people into clearly-defined parties, in a situation where it is very unlikely such extreme divisions would occur naturally.

Honestly, given that set of voters, 90 isn't all that bad a choice. 70 may sound like a nice middle ground, but it isn't according to your data. If just one 70 voter drops out, the median would jump to 80, if another drops out, it jumps to 90. Median obviously fails to give a meaningful result if you have giant gaps right in the middle ground area. Here a reasonable middle ground is more like 78, but median doesn't find that because the data is so extremely (and unnaturally) quantized, with a huge jump right around the 50 percentile.

(If it used interpolated median rather than plain-old median, you'd end up with an answer closer to 78 probably. But I don't think interpolated median would be needed in real world situations with more than a few voters)

In real elections for human candidates, you have an additional effect that doesn't really apply to the temperature thing. That's that candidates that are most electable have more incentive to run. So if the system favors centrists and moderates, more centrists and moderates will be on the ballot. I believe almost all the examples and arguments you have been giving seem to assume that this isn't the case. Not just where no one is voting for any temperature between 70 and 90, but where you seem to be assuming that Black voters simply want at least one Black coalition representative (who will presumably be Black themselves), even if they get a few racists and white supremists elected as well, as opposed to being as happy if all the elected representatives are in a nice middle ground on racial issues.

-

You have many good points there and I'm sorry if I sound like I am brushing them off, but I cannot help but feel like you are ducking the question.

Let's put aside toy examples, mathematical models, and speculation. The facts of real life are

- Alabama voters are highly polarized along racial lines, and this is mostly for historical & social reasons and has little to do with the choice of voting method.

- Districts are being drawn such that Black voters are a majority in only a single district, despite being over a quarter of the population

- Any method satisfying the Majority criterion, including Condorcet, will not give Black voters adequate representation in the legislature. Because of point 1., we do not have to think too hard about what constitutes 'adequate' representation since most voters are simply polarized on racial lines.

And the question is: how can we elect more Black representatives commensurate with the Black percentage of the population without PR? I agree with you that Condorcet is excellent for single-winner elections. But Condorcet + gerrymandering is not excellent for multi-winner elections.

I have also lived in Alabama by the way, about two years in Ft. Rucker, but this was before I was of voting age.

what is "proportional" about PR if it doesn't refer to parties -- or at least distinct, hard-edged clusters. Can that be expressed in a simple sentence?

In layman's terms, these definitions boil down to the idea that any x% of the electorate should control x% of the seats. Basically any collection of ballots, if they constitute at least some number X quotas, and if that collection is sufficiently 'cohesive' (meaning they agree on some candidates), then they deserve at least X elected winners.

Here, 'cohesiveness' does not have to be on party lines, and parties do not even have to exist. The coalitions are determined post-hoc based on how the submitted ballots overlap in support.

-

@rob said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

I'm just saying, dividing people into discrete groups and then trying to deal with it based on group isn't always helpful.

This is true when the groups are imposed by force or external factors, but when people naturally form collectives due to the possibility of aligning their intentions for mutual benefit (and given that said collectives are not going to war with each other...) group behavior can be very, very helpful indeed.

I do understand your issue with the avenues for extremists to impede collaboration. In my conception, as long as there is sufficient diversity in a representative body, the clout behind extreme platforms will not be enough to stop broader decisions from being made. This of course is assuming that the diversity present in the actual population of "electable" candidates for that body has a strong center that can bridge the gaps between more extreme positions. A Condorcet/median seeking method does seem like it would build up a very good bridge, but there doesn't seem to be much of anything on either side of it.

I do wonder about the structure of interparty politics. Do parties have ambassadors for other parties? It seems like something like that would help with a lot of the difficulties.

I mentioned this concept in another thread, but for example, what if there were a coalition of parties, where elected representatives from each party would come in two generic kinds, one being elected internally by members of the party, and others being elected externally by members outside of the party, with some kind of quota of the form "To admit X internally elected representatives, each party requires to admit Y externally elected representatives"? If voters could freely choose party alignment before elections, seats could be apportioned according to party membership, and maybe quotas could be determined by some function of the number of seats apportioned to a party and the number of seats apportioned to every other party.

Maybe for each pair (A,B) of parties, party A requires at least Y representatives elected from party B in order to have X representatives elected from party A. Can you imagine what that kind of thing would do to the democratic and republican parties? They would both be forced to nominate middle ground candidates in order to be allowed to elect their own more extreme representatives. The ratios and seat appointments could be chosen to guarantee proportional representation for complying parties. Under a system like this, parties could only gain representation by accruing membership and by compromising with other parties.

-

@andy-dienes said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

But Condorcet + gerrymandering is not excellent for multi-winner elections.

The incentive to gerrymander should be severely weakened by a system that favors middle ground candidates. The current logic of gerrymandering is all about choose-one and especially in an entrenched two-party system. It's all contingent on systems that have a threshold.... you tweak the boundaries so it tilts enough in your favor to just be enough to win. I don't see how any of that applies with a system that favors centrists, especially when such a system has been in operation for long enough to find a new equilibrium. Gerrymandering would accomplish very little.

@andy-dienes said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

Let's put aside toy examples, mathematical models, and speculation. The facts of real life are

Alabama voters are highly polarized along racial lines, and this is mostly for historical & social reasons and has little to do with the choice of voting method.

Personally I think there's a huge number of flaws in the example and logic here.

The first is that you chose a group for your example that appears (at least at first blush) to have very clear boundaries. Someone’s either black or they're not, for the most part. It makes it easier when you have a situation like that to talk about people having representation, if people fit neatly into a well defined, singular group. But I think that situation doesn't generalize, at all. I'm not even sure it's true for that group: for instance there's always your Kanye Wests and Clarence Thomases and Herschel Walkers who may be black, but align themselves with people who have been very racist toward black people. The example only works with the assumption that being black is the core thing about most black people’s identity and political views, and that there is a good bit of homogeneity within. Should a black person be able to have an opinion on, say, the environment? Do they get to express it in their vote, in any way? Your system means that they their whole vote is about being black and black issues, and if they don't agree with other black people on those issue, they have little way of expressing that.

Secondly you chose a group that is large enough that proportional representation seems like it could work well. Like maybe they're about a third of the population and you have three representatives, so that works out. Obviously that doesn't always work out so well, such as you only have 3 slots to fill and a “natural group” that only has 15 percent of the population. So again, while you may be able to come up with scenarios where it seems to work well, it really isn't generalizable.

(on a side note, I also don't like the example simply because we're mostly a bunch of white dudes here and it forces us to make assumptions about black identity and puts us into extremely delicate territory, which I don't think allows free discussion.)

Finally, there's the fact it doesn't really solve the problem, given that voting within the legislative body still uses majority voting. So let's say you've got 1/3 of the population being black, and 1/3 of the representatives are black. You've just kicked the can down the road, from the voters to the legislators. Blacks are still a minority, using a voting system that is presumably still based on majority.

I think you'd get a lot better results for the black voters if, rather than simply getting one-third of the legislators to be black, you had the legislators that are elected be more toward the center (such as a Condorcet method would be likely to produce), and appropriately taking into account the views and interests of the black voters, whether or not those legislators are actually black.

I guess the main thing that bugs me about it is that, in most cases, it's artificially forcing people into groups, which is what I hate about the system we have now. Maybe it would be more than two groups, and I guess that's better, but I just don't get the need to force people into groups and to entrench those groups.

I want to be seen by the system as someone who has opinions on abortion (e.g. pro-choice but only pre-viability), opinions on economics (e.g. pro-anti-trust, especially with tech companies), opinions on free speech (e.g. social media needs stronger mechanisms to disincentivize divisiveness and misinformation rather than "anything goes"), and so on. I don't like being pigeonholed.

-

@rob said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

I guess the main thing that bugs me about it is that, in most cases, it's artificially forcing people into groups, which is what I hate about the system we have now. Maybe it would be more than two groups, and I guess that's better, but I just don't get the need to force people into groups and to entrench those groups.

Just on this bit, non-party-list PR doesn't force people into groups. You vote for (rank, rate, whatever) whichever of the available candidates you want, regardless of how much in common they might have with each other or which party or group they are perceived as being in. The PR algorithm then just elects the slate of candidates that best represents the electorate (according to its own algorithm). Voters are not then assigned one representative of those elected; they are all available as representatives. E.g. in a region with five representatives they are all "yours". At no point are you forced into a group.

-

@toby-pereira said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

other or which party or group they are perceived as being in. The PR algorithm then just elects the slate of candidates that best represents the electorate (according to its own algorithm). Voters are not then assigned one representative of those elected; they are all available as representatives. E.g. in a region with five representatives they are all "yours". At no point are you forced into a group.

So what is that algorithm? I mean, it could be Condorcet, and I have no problem with that, but I can't see how the term "proportional representation" applies. It just sounds like multi-winner.... there isn't anything proportional about it.

The only way the term "proportional representation" would apply (by my understanding of the term) is if we assume that there are some number of parties, and each candidate and each voter is in one and only one party. If a 3rd of the voters are in the Bull Moose party, then a third of those elected should be in the Bull Moose party. The further you get away from that, the less "proportional representation" seems to be a meaningful descriptor.

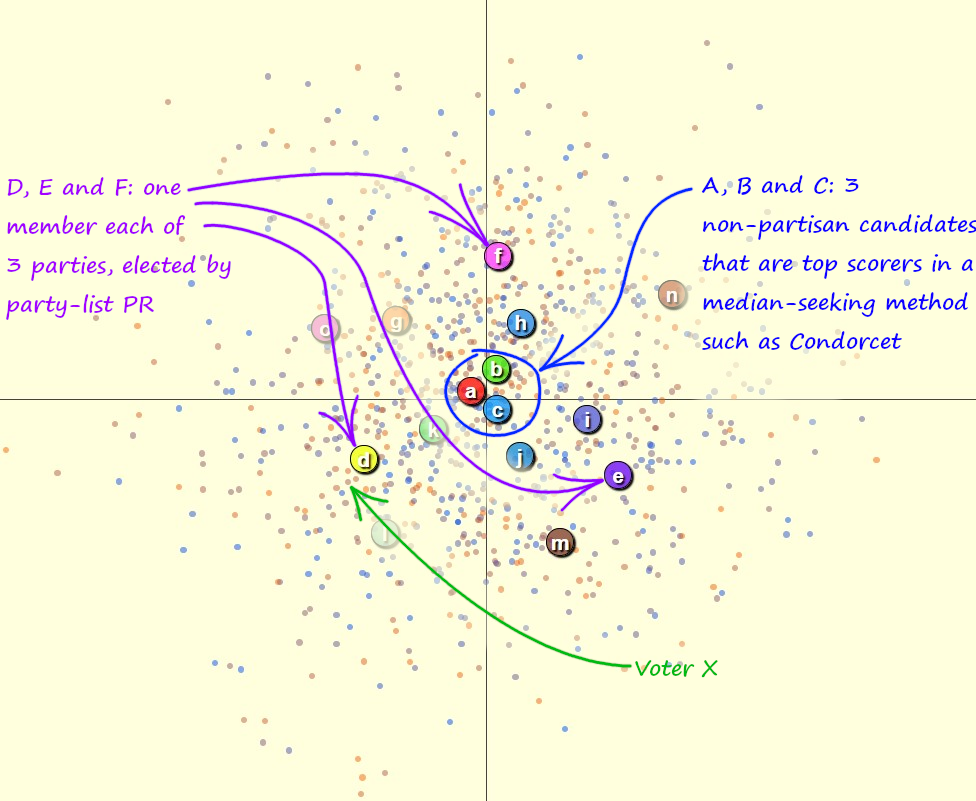

All of my complaints regarding PR (and with so many people's insistence that it is so much better than single winner methods such as Condorcet methods) are based on the assumption that voter X below is considered to have "better representation" if d, f and e are elected (because candidate d is very close to voter X), than if a, b and c are elected.

I would expect a b and c to be elected if they do it via Condorcet. I'm all in on that. Voter X got just as much "representation" (given that the average position of those elected is about the same), but the difference is now you have elected a set of people who are probably going to get things done rather than fight each other.

I just wouldn't call that proportional representation.

-

@rob said in Are Equal-ranking Condorcet Systems susceptible to Duverger’s law?:

So what is that algorithm? I mean, it could be Condorcet, and I have no problem with that, but I can't see how the term "proportional representation" applies. It just sounds like multi-winner.... there isn't anything proportional about it.

The only way the term "proportional representation" would apply (by my understanding of the term) is if we assume that there are some number of parties, and each candidate and each voter is in one and only one party. If a 3rd of the voters are in the Bull Moose party, then a third of those elected should be in the Bull Moose party. The further you get away from that, the less "proportional representation" seems to be a meaningful descriptor.

All of my complaints regarding PR (and with so many people's insistence that it is so much better than single winner methods such as Condorcet methods) are based on the assumption that voter X below is considered to have "better representation" if d, f and e are elected (because candidate d is very close to voter X), than if a, b and c are elected.For the algorithm, you will be aware of Single Transferable Vote, which gives PR without any mention of parties. If voters happen to vote along party lines, it gives party PR, of course. That's just one example, without having to mention obscure methods invented by people on this forum.

And as for a, b, c versus d, e, f, I discussed that in the other thread here. I'm not sure it's worth quoting though because it's quite long.