PR with ambassador quotas and "cake-cutting" incentives

-

This is a concept I had in mind which may already have been described, although not all of the logistics are necessarily hashed out and there may be issues with it. The idea is described below, but first I want to make a connection to “cake-cutting.” The standard cake-cutting problem is when two greedy agents are going to try to share a cake fairly without an external arbiter. An elegant solution is a simple procedure where one agent is allowed to cut the cake into two pieces, and the other agent is allowed to choose which piece to take for themselves. The first agent will have incentive to cut the cake as evenly as discernible, since the second agent will try to take whichever piece is larger. In the end, neither agent should have any misgivings about their piece of cake.

So this is my attempt to apply that kind of procedure to political parties and representatives. Forgive my lack of education regarding how political parties work:

- There should be a government body that registers political parties and demands the compliance of all political parties to its procedures in order for them to acquire seats for representation;

- (Eyebrow raising, but you might see why...) Every voter must register as a member of exactly one political party in order to cast a ballot (?);

- Each political party A is initially reserved a number of seats in proportion to the number of voters with membership in A; the fraction of seats reserved for A is P(A). however

- For each pair of political parties A and B (where possibly B=A), a fraction of seats totaling P(A~B):=P(A)P(B) will be reserved for candidates nominated by A, and elected by B; these seats will be called ambassador seats from A to B when B is different from A, and otherwise will be called the main platform seats for A;

- Let there be a support quota Q(A~B) for the number of votes needed to elect ambassadors from A to B, and call P(A~B) the ambassador quota of party A for B. If E(A~B) is the fraction of filled A-to-B ambassador seats (as a fraction of all seats), I.e. nominees from A who are actually elected by members of B, then A will only be allowed to elect P(A~A)*min{min{E(A~B)/P(A~B), E(B~A)/P(B~A)}: B not equal to A} of its own nominees. That is, the proportion of reserved main-platform seats that A will be allowed to fill is the least fraction of reserved ambassador seats it fills in relation to every other party, including both the ambassadors from A to other parties, and the ambassadors from other parties to A.

This procedure forces parties to also nominate candidates that compromise between different party platforms in order to obtain seats for any main-platform representatives. If a party fails to meet its quota for interparty compromises, it will lose representation. On the flip side, this set up will also establish high incentives for other parties to compromise with them in order to secure their own main-platform representation. In total, this system would give parties high incentives to compromise with each other and find candidates in the middle ground, which will serve as intermediaries between their main platforms.

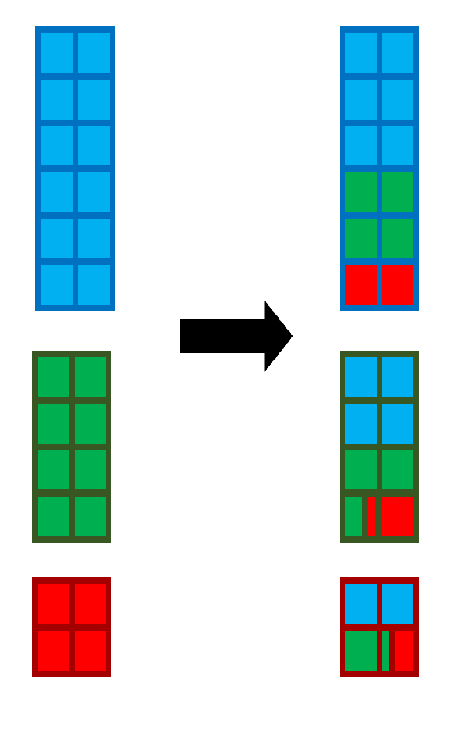

Basically, here the outlines indicate seats open to be filled by candidates who are nominated by the corresponding party, and the fill color indicates seats open for election by the corresponding party:

Seats with outlines and fills of non-matching color are ambassador seats, and seats with matching outline and color are main platform seats. In terms of party A, by failing to nominate sufficiently-many candidates who would meet the support quota Q(A~B) to become elected as ambassadors from A to B, or by failing to elect enough ambassadors from B to A, party A restricts its own main platform representation and that of B simultaneously. By symmetry the reciprocal relationship holds from B to A. Therefore all parties are entangled in a dilemma: to secure main-platform representation, parties must nominate a proportional number of candidates who are acceptable enough to other parties to be elected as ambassadors.

To see that all needed seats are filled in the case of a stalemate, where parties refuse to nominate acceptable candidates to other parties and/or refuse to elect ambassadors, the election can be redone with the proportions being recalculated according to the party seats that were actually filled.

The support quotas collectively serve as a non-compensatory threshold to indicate sufficient levels of inter-party compromise. Ordinary PR is identical to PR with ambassador quotas but with all support quotas set to zero, whereby there is no incentive to nominate compromise candidates.

The purpose of this kind of procedure is twofold: firstly, it should significantly enhance the cognitive diversity of representatives, and secondly, it should significantly strengthen more moderate platforms (namely those of the ambassadors) that can serve as intermediaries for compromises between the main platforms of parties. Every party A has a natural “smooth route” from its main platform to the main platform of every other party: The main platform of A should naturally be in communication with ambassadors from A to B, who should naturally communicate with ambassadors from B to A, who should naturally communicate with the main platform of B.

Also, this procedure gives small parties significant bargaining power in securing representation. Large parties will have much more representation to lose than the small parties that are able to secure seats if the small parties refuse to elect any ambassadors, so rationally speaking, large parties should naturally concede to nominating sufficiently many potential ambassadors whose platforms are closer to the main platforms of those small parties. The same rationale holds for the potential ambassadors nominated by small parties, who also should tend to have platforms closer to the main platform of the small party.

Finally, this system creates significant incentives for voters to learn about the platforms of candidates from other parties who stand to reserve seats for representatives.

-

@cfrank This is interesting, but it does also seem rather complex, so I'm glad you put up the pictures! It also seems as though all the other parties could gang up on one party to force them out, for example.

Also, I'm not sure how the voting would work with this and therefore what reaching the support quota would entail.

-

@toby-pereira yes I agree, thanks for taking a look! I’m curious about your point about parties ganging up, do you have a generic example in mind?

Each party’s main platform representation is limited by the minimum of compliance rates with all ambassador quotas involving that party. So for example, if we have three parties A, B, C, and the compliance rates are

(A~B): 80% of ambassador seats filled

(A~C): 90% of ambassador seats filled

(B~A): 100% of ambassador seats filled

(B~C): 85% of ambassador seats filled

(C~A): 100% of ambassador seats filledthen A will only be allowed to fill 80% of its main platform seats, B will only be allowed to fill 80% of its main platform seats, and C will only be allowed to fill 85% of its main platform seats. So the lack of compromise cuts both ways.

I imagined voting being approval based but with each voter registered under a single party. I figure parties would nominate any candidates they like, and the party affiliations of voters and the party nominations of candidates would determine the filling of “quotas” in some way. For example, if a voter registers under party A, and party B nominates a candidate, I figured a vote cast by that voter to that candidate would contribute to the (A~B) ambassador quota.

I’m now thinking about whether a candidate might be able to acquire multiple seats as ambassadors across many parties. I’m not necessarily thinking of this as a formal decision procedure for how to allocate the seats, but as an apparatus or framework within which seats might be allocated by an additional, more formal mechanism. Does that make sense?

A kind of basic “support quota” for an (A~B) ambassador would be 50%, meaning at least half of the voters registered for party A approved of the B-nominated candidate. B-nominated candidates with less than the support quota from A cannot be given an (A~B) ambassador seat.

-

@cfrank Sorry, I was wrong about forcing a party out. If everyone ganged up on another party so that party had zero support from everyone else it would destroy the other parties too, as it's their minimum that counts.

I think something like approval voting would make sense for this. FPTP would obviously split votes and ruin quotas. With ranks, it's unclear what would count as support.

-

@toby-pereira you were on the right track about something: in this system, small parties can effectively sacrifice themselves to take down larger parties. This could lead to the creation of “puppet parties” that are essentially used as weapons to take down representation of another party, which is kind of a virtual form of MAD warfare.

-

@Toby-Pereira I tried to fix this problem, and came up with some formulas to define the quota compliance multiplier using entropy. It’s kind of complicated, but it’s well-defined, and it encourages diverse compromises between parties. It probably now gives more bargaining power to larger parties, and “puppeteering” can still be strategic, but I think those things are in direct conflict unfortunately.

This is a markdown file that defines the formula.

# Proposed Compliance Multiplier Formula This document presents a proposed formula for the compliance multiplier in the proposed system, which compares the observed distribution of ambassador seats with the ideal distribution based solely on voter shares. ## 1. Partition Functions The ideal partition function for a given party \(X\) is defined as: [ Z_P(X) = P(X \sim X) + \sum_{i \neq X} P(X \sim i) + \sum_{j \neq X} P(j \sim X) ] The observed partition function is defined as: [ Z_Q(X) = P(X \sim X) + \sum_{i \neq X} Q(X \sim i) + \sum_{j \neq X} Q(j \sim X) ] *Note: For party consistency, we impose that \(Q(X \sim X) = P(X \sim X)\) for every party \(X\).* ## 2. Entropy–like Quantities The ideal (maximum) entropy is given by: [ E_P(X) = \frac{-P(X \sim X)\ln P(X \sim X) - \sum_{i \neq X} P(X \sim i)\ln P(X \sim i) - \sum_{j \neq X} P(j \sim X)\ln P(j \sim X)}{Z_P(X)} + \ln Z_P(X) ] The observed entropy is given by: [ E_Q(X) = \frac{-P(X \sim X)\ln P(X \sim X) - \sum_{i \neq X} Q(X \sim i)\ln Q(X \sim i) - \sum_{j \neq X} Q(j \sim X)\ln Q(j \sim X)}{Z_Q(X)} + \ln Z_Q(X) ] ## 3. Compliance Multiplier The compliance multiplier for party \(X\) is then defined as: [ \text{Multiplier}(X) = \frac{E_Q(X)}{E_P(X)} ] Since for every off-diagonal entry we have \(Q(X \sim Y) \leq P(X \sim Y)\) (with equality on the diagonal), the normalized observed entropy \(E_Q(X)\) is less than or equal to the ideal entropy \(E_P(X)\). Therefore, it follows that: [ \text{Multiplier}(X) \leq 1. ] This guarantees that a party's compliance multiplier never exceeds 1, reflecting that the observed (normalized) diversity of ambassador nominations cannot surpass the ideal (maximally spread) distribution.And here are some examples

# Four-Party Examples of Compliance Multipliers This document presents computed examples for a 4-party system under different scenarios. We consider four parties—A, B, C, and D—with the following voter shares: - **Party A:** 0.4 - **Party B:** 0.3 - **Party C:** 0.2 - **Party D:** 0.1 The ideal ambassador seat allocation is given by: [ P(X \sim Y)=P(X) \times P(Y) ] Thus, the **ideal matrix** \(P\) is: | From \(\backslash\) To | A | B | C | D | |------------------------|------|------|------|------| | **A** | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.04 | | **B** | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.03 | | **C** | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | | **D** | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | For each party \(X\), we define the **partition functions** as follows: - **Ideal:** [ Z_P(X)=P(X\sim X)+\sum_{Y\neq X}P(X\sim Y)+\sum_{Y\neq X}P(Y\sim X) ] - **Observed:** [ Z_Q(X)=P(X\sim X)+\sum_{Y\neq X}Q(X\sim Y)+\sum_{Y\neq X}Q(Y\sim X) ] with the assumption that for all parties, \(Q(X \sim X)=P(X \sim X)\). We then define the **entropy–like quantities**: [ E_P(X)=\frac{-\sum_Y P(X\sim Y)\ln P(X\sim Y)}{Z_P(X)}+\ln Z_P(X) ] [ E_Q(X)=\frac{-\sum_Y Q(X\sim Y)\ln Q(X\sim Y)}{Z_Q(X)}+\ln Z_Q(X) ] and the **compliance multiplier** is given by: [ \text{Multiplier}(X)=\frac{E_Q(X)}{E_P(X)}. ] Under the condition that for every off-diagonal entry \(Q(X\sim Y)\leq P(X\sim Y)\), the normalized observed entropy cannot exceed the ideal one—so \(\text{Multiplier}(X)\leq 1\). --- ## Scenario 1: Full Compliance **Situation:** Every party fills its ambassador seats exactly as in the ideal, so for all \(X, Y\): [ Q(X\sim Y)=P(X\sim Y). ] **Results:** - **Party A:** Multiplier = 1.000 - **Party B:** Multiplier = 1.000 - **Party C:** Multiplier = 1.000 - **Party D:** Multiplier = 1.000 --- ## Scenario 2: Sabotage by Party B Against Party A **Modification:** Party B refuses to elect any ambassadors from A. In our observed matrix, we set: [ Q(B\sim A)=0 \quad \text{(instead of the ideal }0.12\text{)}. ] All other entries remain ideal. ### Computed Values **For Party A:** - **Ideal Partition Function:** \(Z_P(A)=0.16+ (0.12+0.08+0.04)+(0.12+0.08+0.04)=0.16+0.24+0.24=0.64.\) - **Observed Partition Function:** - Row A remains: \(0.16+0.12+0.08+0.04=0.40.\) - Column A: Instead of \(0.12+0.08+0.04=0.24,\) we have \(0+0.08+0.04=0.12.\) So, \(Z_Q(A)=0.16+0.24+0.12=0.40.\) - **Entropy–like Quantities (Approximate):** - \(E_P(A) \approx 1.840.\) - \(E_Q(A) \approx 1.472.\) - **Compliance Multiplier:** [ \text{Multiplier}(A)\approx \frac{1.472}{1.840}\approx 0.800. ] **For Party B:** - **Ideal Partition Function:** \(Z_P(B)\approx 0.51.\) - **Observed Partition Function:** \(Z_Q(B)\approx 0.27.\) - **Entropy–like Quantities (Approximate):** - \(E_P(B) \approx 1.824.\) - \(E_Q(B) \approx 1.524.\) - **Compliance Multiplier:** [ \text{Multiplier}(B)\approx \frac{1.524}{1.824}\approx 0.834. ] **For Parties C and D:** No sabotage occurs, so: - **Multiplier(C) = 1.000.** - **Multiplier(D) = 1.000.** --- ## Scenario 3: Puppet Scenario – Party D as a Puppet for Party A **Modification:** Party D acts as a puppet for Party A to harm Party B. We set: [ Q(D\sim B)=0 \quad \text{(instead of the ideal }0.03\text{)}. ] All other entries remain ideal. ### Computed Values **For Party A:** - \(Z_Q(A)\) remains nearly ideal, so **Multiplier(A) \(\approx 1.000\).** **For Party B:** - Losing support from D reduces its observed diversity, so **Multiplier(B) \(\approx 0.910\).** **For Party C:** - Fully compliant, so **Multiplier(C) = 1.000.** **For Party D (the puppet):** - Due to its refusal to elect from B, its observed diversity is reduced: **Multiplier(D) \(\approx 0.940\).** ### Effective Representation for the A Coalition If effective main-platform representation is given by the product of voter share and multiplier, then: - **Party A:** \(0.4 \times 1.000 = 0.400.\) - **Party D:** \(0.1 \times 0.940 \approx 0.094.\) Thus, the total effective representation for the A coalition is: [ R(A \text{ coalition}) = 0.400 + 0.094 \approx 0.494. ] This is slightly less than the 0.5 (50%) of the vote they would control if D were fully compliant, reflecting the cost of splitting support. --- ## Summary of Computed Multipliers - **Scenario 1 (Full Compliance):** - A: 1.000 - B: 1.000 - C: 1.000 - D: 1.000 - **Scenario 2 (Sabotage by B Against A):** - A: ≈ 0.800 - B: ≈ 0.834 - C: 1.000 - D: 1.000 - **Scenario 3 (Puppet – D as Puppet for A):** - A: ≈ 1.000 - B: ≈ 0.910 - C: 1.000 - D: ≈ 0.940 --- ## Interpretation - **Full Compliance:** All parties achieve ideal diversity, so their compliance multipliers are 1. - **Sabotage:** When Party B refuses to elect ambassadors from Party A, both A and B see their normalized diversity reduced (multipliers drop to ≈0.800 and ≈0.834, respectively). - **Puppet Scenario:** Using Party D as a puppet to harm Party B, while A remains nearly ideal, both B and D are penalized—the puppet (D) suffers a lower multiplier (≈0.940) and B’s multiplier drops to about 0.910. Moreover, the A coalition's effective representation becomes slightly diluted (≈0.494 instead of 0.500). These examples illustrate that while parties might attempt sabotage or use puppets to undermine competitors, the system’s reliance on normalized diversity ensures that such strategies come at a cost to all parties involved.I think with careful consideration, it might be possible to adjust the multiplier so that “puppeteering” actually harms a party in proportion to the harm it could cause to its largest rival. For example, maybe raising the multiplier to some power or passing it through some other function would disincentivize puppeteering more.